Date: 06/06/2019

Abigail Croydon, School of Education, University of Southampton

Bradley Tombleson, Gerontology, University of Southampton

Jason Preston, Applied Social Science, University of Brighton

Bea Gardner, Sociology and Social Policy, University of Southampton

Andreea Butnaru, MSc Social Research Methods, University of Southampton

The Task

The first day of the SCDTP residential to Cumberland Lodge was taken up with the ‘Policy Challenge’. Organised by the SCDTP Post Docs, we were split into small groups and tasked with designing a policy solution to the very current issue of knife crime. The topic was introduced by Dr Jason Horsley, Joint Director for public health in Southampton & Portsmouth City Councils. Jason was also the expert judge for the competition, providing a policy perspective on the solutions presented. To meet the challenge, we needed to provide a solution drawn from a credible evidence base, which was ethically considered, innovative and delivered engagingly.

The ‘Wicked’ Problem of Knife Crime

In Jason’s introduction, he outlined that some policy problems involve numerous complex interdependent causes and will never go away entirely. The damage that these ‘wicked problems’ inflict can be minimised, but it is a mistake to assume they can be solved or fixed. Jason described the features of knife crime in these terms – as a multi-faceted societal issue that no single policy could be expected to eradicate completely. Yet the current high political profile of knife crime – especially the age of recent victims and the prevalence of knife carrying – has put policy makers under intense pressure to do something.

Our approach

We started off our discussion using the ‘5 Whys?’ approach, thinking broadly at first and getting more specific as we continued to consider some of the other causes. We used a mind map to document our discussion and the ideas generated. We decided to look at the problem at the community level – issues of poverty, deprivation, disaffection from education, problematic policing and parenting all emerged as leading factors in this discussion. In spite of Jason’s advice that there is no single solution to knife crime, we spent a great amount of time and energy trying to find one. The most challenging aspect was that in the current economic and political environment, many interventions would not be tenable. For example, we spent time discussing various services that have been cut or cut back as a consequence of austerity policies – such as Sure Start – which would be unlikely to be reinstated.

We then moved on to look at more specific research and evidence relating to knife crime. The key findings we took into account were:

- The profile of stab victims – many more aged 10-16 years, risen by over 60% in 7 years (NHS England, 2019).

- The times and places that stabbings occur: 94% on weekdays, 72% in/around schools (ONS, 2017), between 4pm and 8pm, with a spike between 4pm and 6pm for under 16s (Vulliamy et al, 2018).

- The reasons young people give for carrying knives: ‘to feel safe’.

- Role of education in changing behaviour – not the biggest factor but can be important(Foster, 2013).

- Lack of trust of authority figures such as the police, social workers and teachers.

- Ex-offenders may be key role models as they are seen as ‘relatable’ (‘unless you’ve experienced that … Unless it’s happened to you, or someone that you know, there’s no way you can fully understand” (Creaney, 2018).

Our solution- Young people are not the problem but part of the solution

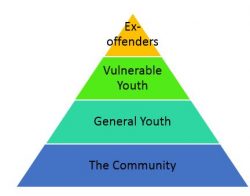

We proposed a ‘bottom up’ approach at the community level, supporting young people themselves to provide preferred after-school activities and to ‘fact-find’ on knife crime or violent crime as it affected their community. We proposed to task older, ‘vulnerable’ youth with designing and running activities for the younger ages, offering them a budget to manage the activities of their choice and paying them to act as supervisors and peer mentors. The older group, in turn, would be supported and mentored by ex-offenders in their youth work and in their research. The basic model is depicted in our diagram below.

We hoped that this format would engage young people in communities affected by knife crime in purposeful activities of their own choice and provide resources to the wider community. It would offer a short-term solution by reducing risk at the critical after-school time points, while having potential to equip young people in the longer term with skills, experience and opportunities through their youth work and their self-education. The benefits – we hoped – would be greater than simply educating the community on issues relating to knife crime. Other stakeholders and local community organisations may wish to invest in the project too, providing expertise and resources.

Concluding thoughts

Our team was thrilled to win, particularly given the quality of the other presentations and policy solutions presented. The trend emerging from the policy proposals was that a ‘solution’ to knife crime is based within the community itself and can only be accessed by engaging with community members directly. Whilst the challenge took all of us out of our comfort zones, the activity showed what can be achieved in a short period of time (3 hours!) when we put our heads together. It also got us thinking about achievable policy solutions in the current economic and political environment. We would like to thank Dr. Jason Horsley for his guidance and feedback, as well as the SCDTP post-docs and organisers for hosting this brilliant event.