Date: 30/11/2022

Zineb Khemissi is an Algerian final year PhD researcher at Portsmouth University, School of Area Studies, History, Politics, and Literature. Funded by the Algerian Embassy in London, her research explores the experience of Korean American adoptees’ identity formation processes within the realm of third space theories. She is interested in history, psychology, literature, and international relations.

Zineb Khemissi is an Algerian final year PhD researcher at Portsmouth University, School of Area Studies, History, Politics, and Literature. Funded by the Algerian Embassy in London, her research explores the experience of Korean American adoptees’ identity formation processes within the realm of third space theories. She is interested in history, psychology, literature, and international relations.

Transnational and transracial adoptions are an ongoing phenomenon that have not received enough interest from within academia. The marketisation of children from poor to rich countries might not be of importance to all, or it might be another reality ‘hidden in plain sight,’ one in which hundreds of thousands of ‘unwanted’ mixed-race children and ‘war orphans’ are de-rooted, displaced, and transplanted into majority ‘White’ backgrounds. Transnational adoption (TNA) is the inclusion of nationally different children within white households (Barn, 2013). Transracial adoption (TRA) refers to adoptees’ different racial and ethnic backgrounds, foregrounding their race as the main concern in the processes of integration and self-identification.

Saving Children by Selling Them

A global market of adoption was established in the aftermath of the Korean War (1950-1953), to ‘save war orphans’ and ‘pitiful victims’ of that tragedy. Such rhetoric emanated from the American discourse of rescue and was emphasized by the media as a solid justification for child displacement. The US is the leading receiving country, while South Korea has the longest programme for international child adoption, spanning over sixty years (McKee, 2016). One reason for the dominance of the US in international child adoption has been the sense of duty of the ‘Christian Americanists’ (Oh, 2015), i.e. a dogma of religious beliefs used during the post-Cold War period as a political justification to obtain the transnational community’s consent for international adoption.

The constant flow of adopted children from poor to rich countries is a lucrative source of revenue that benefits the institutions and organizations that grant child transfers. ‘The Transnational Adoption Industrial Complex’ (TAIC) (McKee, 2016) goes beyond the valuation of human beings, dehumanising children through commodification under the call of capitalist gain. For example, child trafficking offered a source of revenue for the South Korean government; it brought in an estimated sum of US $15–$20 million in annual income (Korean Ministry of Health and Welfare, 2008, cited by McKee, 2016). This commodification is both dehumanising and victimising children.

Defence via Discrimination Route

An important and hidden factor relating to these transfers is the way an adopted child’s personal development is affected through the process of assimilation. Adopted individuals are expected to assimilate into the new culture of their host country, while simultaneously being subjected to racial prejudice and exclusion. However, these experiences of racial discrimination are the engine by which adoptees are pushed toward developing defence mechanisms and coping strategies that shape and define their later strengths.

Self-identification is an important aspect of the identity formation process for adoptees. This process often begins with the individual experience before moving towards more collective identification. For example, identity negotiation and formation can be identified in the process by which adoptees reach out to one another. This can result in a sense of belonging previously absent in the assimilation process. This coming together is important as a healing process, through which adoptees can share their stories, get to know more about their Korean heritage and culture as well as reconcile with it after a long-held denial when the only option left is the assimilation of the American lifestyle and culture.

Korean American Adoptees’ status as ‘outsiders within’ highlights their situation in a third space: an in-between space that comprises two cultural backgrounds. Between victimisation and agency-taking, assimilation and acknowledgment of their differences, colour-blindness, and initiation to their Korean heritage, many changes occur in the lifespan of adoptees. These changes relate to the dynamics of a constantly changing society and parents’ approaches to TNA and TRA.

Discourse Changes Adoptees’ Sense of Self

My PhD research focused on understanding the phenomenon of TNA/TRA through the existing discourses surrounding those processes, and how changes in discourse influenced adoptees’ experiences. Through the lenses of critical discourse studies (CDS), which refers to the use of an eclectic selection of approaches to discourse analysis, I first scrutinised media portrayals of TNA. I then set up a theoretical model to understand adoptees’ experiences and how different generations dealt with the collective trauma of abandonment and loss in their own distinct ways. I also explored how different approaches to TNA/TRA form a distinct experience for adoptees and how changes in society accompanied these changes in experience.

The intergenerational aspect of my research extended over 50 years, from the 1950s to the 1990s. The post Great Depression period, the WWII-era, and the Baby Boom period, extending from 1946 to1964, saw a return to a society built upon a framework of Christian values. This consisted of social emphasis on the family and the redirection of societal attention to the domestic spheres. Meanwhile, the rise of the suburban neighbourhood provided a new alternative for middle-class families to escape big-city crowds, thus, establishing a visible change in American society.

In the 1950s and 1960s, America was known for its racial rejection, a phenomenon that is still present and identifiable in the ongoing resistance to it through the Black Lives Matter movement. Yet, white Americans often claim to be ‘colour blind’. This American colour-blind perspective has provided the means through which Korean Adoptees could be integrated within American society. The mid-1950s to the 1960s saw different civil rights movements, feminism, anti-segregation, and anti-racism; hence, a more inclusive approach towards racially different people started developing in America from the mid-1960s onwards.

TNA Diminished But it Isn’t Finished!

The Civil Rights Act of 1964 came as a result and means of outlawing discrimination based on race, colour, sex, religion, or origin requiring equal access to public spaces and work opportunities. The 1970s and 1980s heard the call for laws of integration with a more inclusive society. The last decade I included in my research was the 1990s, which saw a decline in the number of adoptions from Korea, following the 1988’s Olympic games ‘baby export’ scandal. This does not infer the end of TNA, yet it marked a considerable decline in the annual number of adoptees from South Korea.

During the post-baby-export scandal period, adoptions from South Korea decreased. However, they did not cease; a considerable number of placements per year are still there to maintain a constant flow for the sustainability of the adoption market. This is evidenced through US government statistics, which trace the numbers of adoptions on an annual basis from different countries (US Department of State, n.d.). The constant flow, even if it comprises a small number of adoptees from sending countries, still contributes to a minimum economic revenue and as a source of capital for those countries undertaking the global transfer of children (Kim, 2012; McKee, 2016).

Profit vs Healthy Adoptees

The movement toward a more inclusive environment does not infer the complete eradication of racial prejudices against minorities. Identity is such a complex notion everyone struggles with, yet we do not all have to deal with more than one background and culture. Reconsidering the issue of TNA in terms of displacement, estrangement, and identity formation difficulties leads us to reconsider this global practice that has been ongoing for nearly seventy years. Is the call for economic opulence more important than providing a healthy growth environment for children?

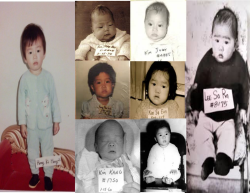

Children’s commodification collage of pictures