Date: 02/05/2019

Ben Brindle is an SCDTP-funded student in Economics. His PhD explores whether previous UK studies have failed to detect adverse wage or employment effects of immigration because the labour market adjusts by alternative means. Other research interests include environmental economics and development in emerging economies. Ben currently works as an Associate Lecturer at the University of Brighton and has previously written for The Times in both the Business and Register sections of the paper.

Since the financial crisis, workers have seen their wages adjusted for inflation grow sluggishly, with forecasts from the Office for National Statistics suggesting the average UK worker will earn less in 2021 than in 2008.

One of the key reasons cited for this stagnation has been the rapid rise in immigration over the past two decades. Net migration rose from 48,000 in 1997 to 282,000 in 2017 (although peaking at 332,000 in 2015). This explanation for wage stagnation has even reached the Prime Minister, Theresa May, and the leader of the opposition, Jeremy Corbyn. However, the reality is more complex.

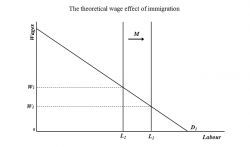

Firstly, we need to understand the theory behind the claim. As Lewis (2017) shows, if the quantity of labour employed in the domestic economy is currently at L1, an influx of migrant labour the size of M will increase the size of the available labour force to L2 and, in turn, increase the level of competition between workers. Employers are now able to “play off” the labour force and hire workers at a lower level of wages (W2 rather than W1).

This model, however, is rather simplistic and has a number of shortcomings. Firstly, it ignores the fact that immigration doesn’t impact the wages of all workers equally. In reality, while immigration will increase competition and decrease wages for those “substitutes” with similar skills, it will raise the productivity (and the wages) for those “complements” with different skills. For example, the addition of a secretary to handle paperwork might free a doctor up to spend more time with her patients.

This is important as immigrants and natives have culture-specific skills and differ in terms of their abilities, motivations and tastes. As a result, the two groups are imperfect substitutes and will tend to enter different occupations, reducing the level competition with each other. In fact, Manacorda et al. (2012) found that this lack of substitutability meant the only group whose wages are affected by immigration are migrants that are already here.

Secondly, the model does not consider the potential for immigration to increase the demand for labour. Dustmann et al. (2008) note that there are at least two ways this may happen. First, immigration may change the mix of goods and services produced in the economy. For example, an increase in the supply of low-skilled labour will drive an expansion of those industries that use low-skilled labour intensively.

Alternatively, immigration may change the technique used by firms to produce goods and services. For example, firms may adopt skill-intensive production techniques in response to an increase in the supply of high-skilled labour. What’s more, this new production technique may involve the use of technology that raises the productivity of those workers now in high supply, raising their wages above the level they were before immigration!

While evidence of these labour market adjustments – particularly technology changes – has been found for the US, Germany, and Spain, no study has yet examined whether this occurs in the UK. My thesis will contain the first study to do so.

The time it takes for these alternative labour market adjustments to occur is determined by wider economic conditions. Employers will readily recruit to expand their production in periods of economic expansion but will be more reluctant in periods of recession, for example. The highly flexible nature of the UK labour market – only less flexible than the US and Canadian labour markets – is also influential, and suggests that adjustments will occur swiftly. But, as we saw earlier, natives’ wages might not even be affected in the short run.

After considering all of the wider influences (which are omitted from the supply shock model and public debate on immigration), it is no surprise that study after study finds wage impacts to be miniscule or, in most cases, non-existent. It is crucial that these facts reach the public debate sooner rather than later, because if the government’s objective to reduce net migration to 100,000, an arbitrary number, remains in place, it could, according to Jonathan Portes, reduce UK productivity and GDP per capita by 1 to 3 per cent by 2030. Far from immigration depressing natives’ wages, reducing immigration could depress natives’ wages.