Date: 26/08/2025

Decoloniality in Motion: African Knowledge at the Crossroads of Marginalisation and Revival – Reflections from a Decolonial Trip to Mombasa, Kenya

Author: Sixtus Onyekwere, University of Portsmouth

Bio:

Sixtus is a PhD student in International Development at the University of Portsmouth, UK. His research, funded by the South Coast Doctoral Training Partnership (SCDTP), examines the effectiveness of NGO, government, and community programmes in preventing Violence Against Women and Girls (VAWG) among internally displaced persons (IDPs) in Nigeria, with a focus on the challenges faced during the COVID-19 pandemic. Sixtus’s core research interests include the intersection of conflict and gender, development aid effectiveness, and NGO interventions in sub-Saharan Africa.

Introduction

In November 2024, I had a great opportunity to visit Mombasa, Kenya, as part of a decolonial research initiative organised by the South Coast Doctoral Training Partnership (SCDTP). This journey was more than just an academic exercise; it was an immersion into histories of resilience, cultural survival, and the ongoing struggles against neo-colonial influences. It came at a critical juncture in my PhD journey, as I grappled with the challenge of reconciling the dominant frameworks and theories in my field with the lived realities, cultures, and traditions of my country of study. The dissonance between these perspectives had begun to trouble me deeply, keeping me awake at night as I questioned whether my research was truly meaningful and impactful or merely another extractive academic exercise. This trip became a crucial step in my pursuit of decoloniality, reinforcing my commitment to producing research that addresses real societal challenges rather than perpetuating intellectual colonialism.

This was me boarding the flight to Mombasa, Kenya with loads of excitement!

A few weeks before our departure, Prof. Tamsin Bradley, SCDTP deputy director, challenged us to reflect on key questions about decoloniality that we hoped the trip might help answer. Some of the burning questions I carried with me included: What does it mean to decolonise knowledge? As Africans trained in Western education systems from undergraduate to PhD levels, thereby navigating dual identities, what role can we play in advancing decoloniality? Why has Africa struggled to establish localised epistemologies that truly reflect its own contexts? Do my research practices contribute to marginalising African knowledge systems, or do they help advance them?

Hopefully, by the end of this blogpost, I will have offered meaningful reflections on these questions, drawing from my readings and insights gained during the trip. Hence, this short piece aims to contribute to the ongoing discussions on decoloniality, challenging us to critically assess our roles in shaping, preserving, and amplifying African knowledge systems

The Shadows of Colonial Legacies: Who Controls Knowledge?

As we began exploring the colonial fingerprints in Mombasa, the questions that I set off with began gaining life. One moment that deeply resonated with me was standing within the walls of Fort Jesus, a fortress built by the Portuguese in the 16th century to exert control over the East African coast. As I walked through the weathered walls of the fort, listening to the tour guide recount the histories of conquest, from the building of the structure by the Portuguese to the arrival of the British, and the Germans, I could not help but think of the countless lives of Kenyan descent that had been shaped, disrupted, and even lost within these very walls. The structure stood not just as a relic of the past but as a stark reminder of the colonial systems that continue to shape contemporary Africa, including its academic institutions.

Image of me standing by Fort Jesus in Mombasa after a tour of the fortress

Once a site of violence and displacement, Fort Jesus now stands as a testament to both the suffering endured and the resilience of African societies. It reinforced, more than ever, the urgency of reclaiming our narratives and rewriting our histories on our own terms, breaking free from imposed perspectives and restoring the integrity of African knowledge systems.

Yet, even amidst this resilience, the deep entanglements of neo-colonialism remain glaring. From the legacies of Western modernisation ideologies to the loss of identities, culture, and languages. Nowhere is this more apparent than in academia, where theories, frameworks, and epistemologies from the Global North continue to dictate knowledge production in African contexts. This hegemony of Western paradigms is evident in the structure of African universities, research funding, and the academic publishing industry, which often privileges Euro-American perspectives while marginalising indigenous and localised knowledge systems.

One of the starkest examples of this is citation politics. African scholars often need to engage with and cite Western theorists to be taken seriously, even when those frameworks do not align with African realities. This is in line with Arowosegbe’s position that knowledge neo-colonialism by the West continues to perpetrate what he called ‘Afro-pessimism’; the view that Africans and African societies are backward and have no potential for progress or creating something worthwhile (Arowosegbe, 2014). This Afro-pessimism’ notion however seems ironic when research funding remains largely controlled by institutions in the Global North, influencing research agenda and priorities in Africa (Connell, 2007). Again, the dominance of the English language in academic publishing further limits accessibility and recognition of indigenous scholarship, reinforcing a knowledge hierarchy where African epistemologies are devalued or dismissed.

Reclaiming African Epistemologies: Can Academia Truly Be Decolonised?

Image of me posing for a photo during our visit to Pwani University, Kenya

Decolonising knowledge is not just about resisting Western influence; it’s about rebuilding intellectual traditions that honour African ways of knowing. Consequently, there has to be a systemic shift from what Mbembe tagged as the ‘Eurocentric Canon’ ; Canon that attributes truth only to the Western way of knowledge production (Mbembe, 2016)’ I witnessed this Eurocentric Canon’ first-hand during the trip when a senior lecturer from one of the Kenyan Universities who was one of the resource persons for the decoloniality trip, lamented during a chat we had with him on the influence of colonial systems on African universities and knowledge production. The lecturer painfully revealed that despite writing so many books, the university has refused to recognise any of these books as resource material for students, meanwhile western authors continue to dominant the faculty even when they are outdated. This is a systemic way of marginalising African voices and authors, and it is saddening that it is also being orchestrated by the very people who should be standing against it. This shows how deeply rooted the Eurocentric Canon’ has established itself within African society.

Nevertheless, the resilience of the lecturer and many other African authors supporting indigenous epistemologies in knowledge production whether acknowledged or not is a stark evidence that African knowledge systems are never lost, they are being constantly marginalised.

Historically, African societies have always had rich traditions of knowledge production. From the novel work of Ngũgĩ wa Thiong’o on Decolonising the Mind, we appreciate that oral histories, storytelling, community-based learning, and spirituality have all played central roles in meaning-making in African contexts (Ngũgĩ, 1986). Yet, these traditions are rarely recognised in mainstream academia. We experienced the beauty of African knowledge system first-hand in our visit to the Mijikenda kaya cultural preservation centre through stories told by one of the elders from the village. His oral history was precise, engaging, and mentally stimulating.

Nevertheless, just like the Mijikenda Kaya cultural preservation centre, several institutions are challenging this status quo from a structural level. Hence, there is promising progress in decolonising knowledge. For example, The Council for the Development of Social Science Research in Africa (CODESRIA) has been at the forefront of promoting African-led scholarship. Similarly, initiatives like the African Studies Association of Africa (ASAA) provide platforms for scholars to engage with knowledge production on their own terms. Universities such as the University of Cape Town’s Decoloniality Project and Makerere University’s African Studies Centre are actively working toward integrating African epistemologies into research and curricula. These institutions need to be supported, as they stand as beacon of hope for advancing decolonial research in Africa

A Personal Reckoning

Listening to scholars like Dr. Hassan Mwakimako, Dr. George Gona, and Dr. Kathleen Anangwe during the trip was a transformative experience. Their thought-provoking lectures forced me to confront my own academic practices, which have been deeply embedded in Western intellectual traditions. As they spoke, I found myself grappling with fundamental questions: Whose knowledge is privileged? Whose voices shape the frameworks we use to understand the world?

Coming from an African background yet having pursued my entire university education in the West, from my undergraduate studies to my current PhD, I often find myself caught in a space of epistemic tension. How do I reconcile the Western theories, concepts, and methodologies I have been trained in with the lived realities of African societies? Until now, I had unconsciously operated under the assumption that these Western paradigms were the gold standard for knowledge production, universal, objective, and unquestionably valid.

This trip, however, disrupted that assumption. It prompted me to engage more deeply with decolonial literature, and the more I read, the more I began to see the world through a different lens, an African lens! I started questioning not just what I had learned, but also what had been omitted from my academic training. Where were the indigenous African philosophies, the knowledge systems rooted in oral traditions, the ways of knowing that had existed long before colonial encounters?

The answers were not far-fetched as I discovered the works of Ngũgĩ wa Thiong’o on Decolonising the Mind, who argues that colonial education systematically erases indigenous ways of knowing by imposing Western languages and epistemologies (Ngũgĩ,1986). Similarly, Santos (2014) describes this process as epistemicide, the deliberate destruction of non-Western knowledge systems. Reflecting on these ideas, I began to see that decolonisation is not just about critiquing colonial history but also about reviving and legitimising knowledge systems that have been historically dismissed.

The work of scholars like Ndlovu-Gatsheni (2018) has further deepened my understanding of the decolonial struggle. His concept of the “coloniality of knowledge” explains how colonial power structures continue to shape what is considered valid knowledge today, long after political independence. He challenges us to rethink academia itself, not just in terms of content but in its very structure and hierarchy.

Image of me chatting with the Mijikenda Kaya storyteller about the similarities of the stories he told with those told by my late grandfather in Nigeria

Beyond theory, I witnessed first-hand in Kenya how decolonisation is not just an abstract academic concept but a lived reality. At the Mijikenda Kaya Cultural Preservation Centre, the indigenous people shared their struggles towards establishing their cultural identities and heritage amidst the aggressive influence of western civilisation. The oral histories shared by the elders resonated deeply with own upbringing in Nigeria. Their narratives, filled with ancestral wisdom, mirrored the stories my late grandfather told when I was around eight years old, tales of communal solidarity, indigenous governance, and spiritual philosophies that predate colonial disruptions. These similarities reaffirm the idea that Africa was once a culturally and intellectually unified space before colonial borders fragmented it (Diop, 1989).

Despite centuries of colonial erasure, these oral traditions persist, passed down through generations as a testament to the resilience of African knowledge systems. The continued existence of such narratives highlights that African epistemologies are not extinct but have been systematically marginalised by dominant Western frameworks of knowledge production (Dei, 2011). By reclaiming and validating these indigenous knowledge systems, we move closer to undoing the epistemic injustices of colonialism.

My shift in perspective is not just an intellectual exercise; it is deeply personal. It challenges me to unlearn and relearn, to interrogate the ways in which colonial legacies continue to shape the production and dissemination of knowledge. It is a journey of reawakening, one that requires humility, openness, and the courage to question deeply entrenched academic norms. Moving forward, I am committed to integrating African epistemologies into my research. This means amplifying African voices, citing African scholars, and challenging the assumption that knowledge must be validated by Western institutions to be legitimate. As the Ghanaian philosopher ‘Kwasi Wiredu’ suggests, true intellectual liberation requires us not only to decolonise knowledge but also to reclaim the agency to define our own intellectual traditions (Wiredu, 1998).

Towards Decolonising Knowledge Production in Africa: Practical Solutions

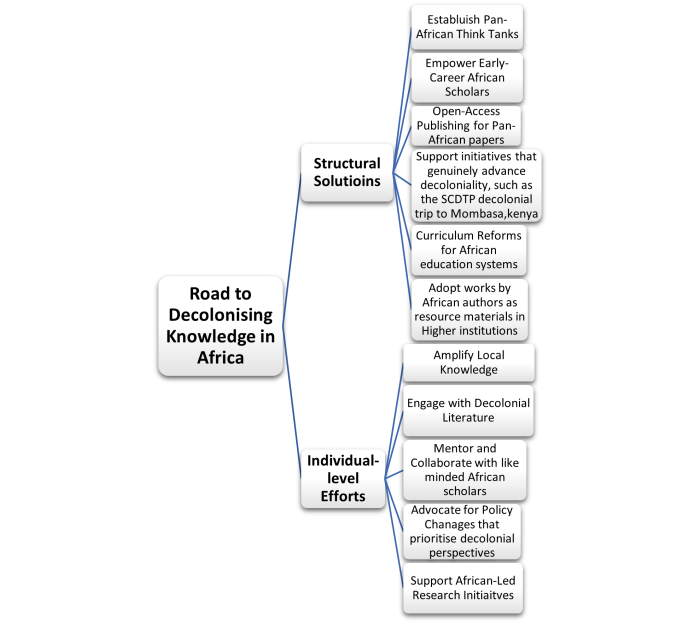

The work of decolonising knowledge is far from over, but it is a journey that requires collective effort at both individual and structural levels. Meaningful change can only be achieved when scholars, institutions, and policymakers actively engage with decolonial perspectives and challenge the dominance of Western epistemologies in African knowledge production.

Source: Author

Individual-level Efforts

At the individual level, engaging with decolonial literature is a crucial first step. There is a need to engage with and amplify African scholars such as Walter Rodney, Ngũgĩ wa Thiong’o, Achille Mbembe and many others which provides critical insights into the struggles against colonial legacies. Beyond simply consuming these works, scholars and students alike must actively seek out African-led journals and research projects, contributing to platforms like CODESRIA and the African Studies Association of Africa (ASAA). Supporting African-led research initiatives ensures that knowledge is produced and disseminated on African terms rather than being filtered through Western academic gatekeeping.

Advocating for policy changes within academic institutions is another essential step. Those within universities should push for curriculum reforms that centre African epistemologies and promote the works of African philosophers, historians, and social theorists. Additionally, research funding bodies must be encouraged to support projects that prioritise local knowledge systems rather than reinforcing Western paradigms. Mentorship also plays a significant role in advancing decoloniality. Established scholars should guide early-career researchers interested in decolonial perspectives, while students can foster peer collaborations that question existing academic structures and explore alternative ways of knowledge production. Knowledge decolonisation also extends beyond formal academia, supporting storytelling, oral histories, and community-driven research acknowledges that indigenous knowledge is not confined to books and journal articles but lives in everyday experiences, cultural expressions, and local traditions.

Structural Solutions

On a broader structural level, African universities must take decisive steps to embed indigenous knowledge systems into their curricula. Decolonisation cannot be fully realised if African academic institutions continue to prioritise Western theories and methodologies while side-lining homegrown intellectual traditions. Establishing Pan-African think tanks is another critical measure. Too often, research in Africa is dictated by foreign grants, which shape research priorities in ways that do not always serve African interests. Many African Think Tanks have become vehicles for advancing Western-led research agendas, reinforcing Afro-pessimistic narratives. To counter this, there is an urgent need to establish research bodies that focus on African heritage and knowledge production while rejecting extractive and exploitative research priorities.

Open-access publishing must also be expanded to ensure wider dissemination of African scholarship. Supporting African journals, publishing research in local languages, and making academic work accessible beyond elite institutions can help democratise knowledge. Additionally, empowering early-career scholars is essential to sustaining the decolonial movement. Young researchers must be encouraged to engage with decolonial perspectives and challenge citation politics that continue to marginalise African voices. Mentorship programs that prioritise African-led research and knowledge production will help shift the academic landscape towards a more equitable and self-determined future.

Finally, while much of the responsibility for decolonisation lies with African institutions and scholars, Western institutions also have a role to play. They should continue to support initiatives that genuinely advance decoloniality, such as the SCDTP decolonial trip to Mombasa. These kinds of programmes create opportunities for critical engagement, fostering collaborations that centre African perspectives rather than reinforcing asymmetrical knowledge production. By funding and facilitating such initiatives, Western institutions can contribute meaningfully to undoing historical injustices and ensuring that decoloniality is not just a theoretical discourse but a lived and transformative process.

References

Arowosegbe, J. O. (2014). African studies and the bias of Eurocentricism. Social Dynamics, 40(2), 308–321.

Connell, R. (2007). Southern theory: The global dynamics of knowledge in social science. In Southern Theory: The Global Dynamics of Knowledge in Social Science. Taylor and Francis.

Dei, G. J. (2011). Indigenous Philosophies and Critical Education. Peter Lang.

Diop, C. A. (1974). The African Origin of civilization: Myth or Reality. Lawrence Hill.

Mbembe, J. A. (2016). Decolonizing the university: New directions. Arts and Humanities in Higher Education, 15(1), 29–45.

Ndlovu-Gatsheni, S. J. (2018). The dynamics of epistemological decolonisation in the 21 st century: towards epistemic freedom. Strategic Review for Southern Africa, 40(1).

Ngugi, W. T. (1986). Decolonising the Mind: The politics of Language in African Literature. https://www.humanities.uci.edu/sites/default/files/document/Wellek_Readings_Ngugi_Quest_for_Relevance.pdf

Santos, B. de S. (2015). Epistemologies of the South: Justice against epistemicide. In Epistemologies of the South. Routledge.

Wiredu, K. (1998). Toward decolonizing African philosophy and religion. 1(4). https://journals.flvc.org/ASQ/article/view/136492